Published June 16th, 2008

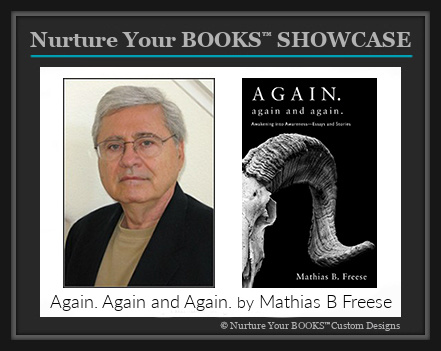

Mathias B. Freese’s short story collection, Down to a Sunless Sea (Wheatmark, 2007), recently received an Independent Publisher Excellence Finalist Award, and was also named a finalist for the Reader Views Literary Award, as well as a finalist in the “popular fiction” category of the 2008 Arizona Book Awards, sponsored by Arizona Book Publishing.

A teacher and psychotherapist, Freese is the author of the four books of the i Tetralogy (Hats Off Books, 2005) — i, I am Gunther, Gunter’s Lament, and Gunther.

Freese hold masters degrees in secondary education and social work from Queens College of the City University of New York and Stony Brook University. For more than 30 years, he taught English and social studies in New York secondary schools.

Freese’s nonfiction articles have appeared in the New York Times, Voices: The Art and Science of Psychotherapy, and Publishers Marketing Association Newsletter. In 2005, the Society of Southwestern Authors honored Freese with a first-place award for personal essay.

Derek Alger: Your recent story collection, Down to a Sunless Sea, has received high praise, not to mention being named a finalist for the Reader Views Literary Award and receiving an Independent Publishers Excellence Finalist Award.

© Mathias Freese

© Mathias Freese

Mathias Freese: The book reflects 30 odd years of a struggle to get published. I made a pact with myself more than two decades ago, I would someday publish a book that contained all my short stories, but they would have to be published in order to prove their worth. Not all were published, but in that pact made with myself is a statement about myself. I will not quit on you, on myself: it is characterological. To receive praise at 67 is a cosmic joke, wouldn’t you say? How would you, dear reader, deal with it? It bespeaks a sad ruefulness not defeated by that very compound; for the next morning light makes me greet the day for being alive. In the midst of my despair, or merry depression, is a force in love with life, alas, no control over the DNA in my flesh. It wills out when I don’t want it to.

DA: What was your childhood like?

MF: I am a passive-aggressive personality which, to my eyes, means that I took in as a child without metabolizing. The undigested, rageful parts spewed out like Ahab’s leg from Moby Dick’s mouth, from time to time. I was a receptor as a child. I did not experience my life so much as observe it, if that. I just associated to the earth bombarded by neutrinos that stream right through the core and out without nary one of us on to it. I reflect on all this in the title story of my book of short stories, Down to a Sunless Sea.

I was raised in the bland soup of benign neglect which did not give me enough sustenance to arm myself for life ahead. A weak father, a depressive for a mother, I later realized that my father was the third child in our family of four. And that my mother had married down, which suited her just fine, because that gave cause to her depression, all insights that came decades later.

We were lower middle class Jewish poor. I never experienced being poor — I ate, I was clothed, there were needs met. Allow me to share an anecdote about my parents and our status in life, all in one ball of wax. My parents worked for two or three days, not including the weeks and months before, to have me ready for my bar mitzvah. It was not catered. We could not afford that. So mom cooked several turkeys and all the Jewish trimmings. At that time, I had a Lionel train set which was increasing in size each year as my two uncles contributed by giving me locomotives and tenders and so on. My father took me aside and said that would I mind if he sold the train set to get additional money to pay for the bar mitzvah. I, of course, said yes, as I had no inner reference at the time, and this was the Fifties, parents as godhead. So an early choice that made me surrender something dear in order to acquire something less dear. I observed all this. I did not feel it until later. I miss those trains. It was a patrimony I would have passed down to my son and daughter. Anyone out there who wants to write a story about this?

DA: Did you always think like a writer?

MF: I don’t really know what it is to think like a writer. I think Matt. I came to writing out of pain, in small acts of serendipity. My first writing was an extended poem that I submitted to the high school yearbook in 1958, which was accepted. However, the English teacher misread it, edited so much out that it was significantly reduced and I had my first experience with editing, poor at that. The poem dealt with my inner depression, as I look back at it now, and that was overridden to give it a bluebird ending. In 1958, the word Holocaust had not entered the language, so what do you expect?

I still don’t know what it is to think like a writer. I am an autodidact, self-taught, no MFA (I’m lucky). I escaped conditioning. I believe to become a great writer or a very good one the writer must avoid organized teaching. I think like a shrink, a father, a lover, a mensch, but not as a writer. When I come to write, I go inward, very inward, and I allow my unconscious to blast through, often ooze, into awareness; that is how I write. I count on all the rules I’ve broken, all the errors I’ve made over 40 years. I count on who I am. I write for me and no one else. I am very serious about what I write. I was a very serious child, I believe now, with a superego, alas, the size of New Jersey. I still am serious. I have no time to write dreck.

You labeled isolation and confusion over the nature of life as the twin tracks in my book of short stories. Allow me to consider that. I was isolated as a child and very confused about the nature of the world itself as I was left to my own devices. I was a bright, perhaps very intelligent child, who was left to lie fallow, to wit, the nutrients ultimately drained from out the fields. I was also alone. It took me decades to learn to dwell in that without fear. I am very inner-directed now. I do not recall having my parents ever embracing me with grand affection, enjoying the mere existence of my being. There was little physical — or verbal! — affection and so, as young people do, I assumed there was something wrong with me. I was marginal. I experienced myself as cold — far from it, but then, yes. Again, I do not start out as a “writer” to deal with such themes; I just allow myself to coalesce and then clot, not really concerned too much with plot, literature’s device for making us happy and contented readers.

DA: The concept of moral courage obviously shaped your world view.

MF: In Hebrew School, I learned a great deal about moral courage; the first book I ever was given, by Grandma Flo, she of vaudeville, was called Jewish Legends. I devoured that book. It entered my bloodstream. Almost 50 years later the legends became part of a dream sequence in my major work, The i Tetralogy. They were that significant. Allow me to make a tangential observation: at least in my too assimilated Jewish family, a book or encyclopedia would be given as a gift but with no follow-up. My father once brought me a violin. I was perplexed. Was I to start playing it without instructions? Am I a genius? It took me years to fathom the aimlessness of the gift, for it lacked nurturance, the oil of relationship.

Shadrach, Meschach and Abendigo obviously caught my attention, for they were morally stronger before their sentence to be consumed by the flames. I offered that to the readers decades later in the Tetraology, writing “What was in them before that made them so fearless? That is the question to ponder.” I was also tested at 13 by an anti-Semitic experience which was indelible. I describe that in detail in my book as well. The key point was that I became a defender of the faith without realizing it. The conditioning as a Jew had settled upon me and I was tested very young. I value Churchillian courage, the courage of the Hebrews in the early texts; I taught myself, on some primal levels, to know who I was and to honor it and to stand up to it. I am in debt to the Hebraic tradition.

The prophet Nathan comes down from the hills, enters the palace, and tells David off to his face about Uriah’s death and his fornication with Bathsheba. My hope is that I could do that without god behind me — that is balls. However, the lesson was not lost upon me; that we are alone; that our worth comes from within; that we seek justice and give it; that fear must be dispensed with while we quake from it. So, if an alien dropped down from the sky and greeted me, I’d probably stroke out; however, I’d go up against any hundred Nazis in a herd.

DA: You say a major revelation about yourself came when you were about thirty?

MF: I advanced as a human being when I met Rochelle. In 1969-70, I was in therapy, and she had been in therapy for several years and it definitely showed. I was wired, unsure, reeling from a disastrous first marriage and a damaging financial onus. The anecdote is basic: I asked Rochelle what she thought of a tie I had put on and she said that it was very nice. In my neuroticism I challenged her, and said, in effect, to cut it out and tell me the truth. It was a classic defense in action — en garde! Her response was part gesture, part words; stepping toward me, she looked at me caringly and said that it was, indeed a very good-looking tie. I was disarmed. I had been told the truth twice and each time rendered tenderly, sincerely. I was married to Rochelle for 29 years until she died in a horrific car accident in 1999. Rochelle nurtured me with respect, she was kind to me, she gave me all the ingredients that I needed to grow. Grades in a master’s program became only A. I began to write better, four years into our marriage, my first significant story was published, “Herbie,” which is in my present collection. I was listed with Norman Mailer, Isaac Bashevis Singer, and Joyce Carol Oates in an anthology of short stories, edited by the famous Martha Foley, bless her soul. So, a nurturing marriage provided me with insight into myself and love.

The value of that experience was to see the failure in not selecting an occupation or profession that was more suitable. How can you do that unless you know who you are?

A shrink said to me once, with consternation, “Why in the world are you a teacher?” In short, she thought I could have done better for myself. (Because I didn’t know any better; because I did not have counseling or healthy parental input.) I thought safe and became ensconced in schools. What is more neurotically safe than tenure?

DA: You taught high school English and social studies in New York City. What was the value of that experience?

MF: “Nicholas” is one story that represents dismay; “Young Man” is a description of my despair as well. I hated it, yet I was terrific at it. You can’t keep the life force down. I wrote throughout the years I spent in the penal colony. I got two articles about my experience in one high school published in the New York Times — that poisoned my relationship with other teachers for years. Acting out, I enjoyed the turmoil, for what I had said was devastatingly true. I think of Alceste in The Misanthrope.

I ran an alternative high school for several years and that was exciting, but it lasted for a short time and was knocked down. I was a New York Jew in Suffolk County, the land of the nouveau riche. Although I have a few good memories of teaching, I rue the experience as wasted except for the serendipitous rewards one gets from it. Teachers in public schools are as much slaves as their students, except, unlike their students, they are castrated. Frank McCourt says much the same thing about his teaching “career.”

DA: What prompted you to become a psychotherapist?

MF: To know. Pain. Intellect. I became a therapist to learn about myself and if I learned enough, like a good Jew, I would share it with you as well. I was intellectually ambitious.

At times a morose thought haunted me: is that all there is? — ending with a stone that says teacher. I wanted to grow, to come to the end of my days with a better appreciation of who I was and what I could do. So I became a teacher, writer and psychotherapist, and they bind together as a triple helix, brushing shoulders here and there to produce better thinking, better writing, a better living existence. I am not driven, how appalling. I am a seeker. “Reach what you cannot,” Nikos Kazantzakis’ Cretan grandfather advises (Report to Greco).

I live with that injunction; I had settled for a while with “Reach what you can.” As I look back, I also remember reading Freud, not understanding much, but reading him in my college days for “fun.” Moses and Monotheism and his book on DaVinci are real mind pleasures. Years later I was interviewed by Robert Langs, a Freudian psychoanalyst, for his book Madness and Cure. I was Mr. Edwards. The upshot was that I fought off a crazy shrink unconsciously and consciously; Langs saw into me pretty well …

DA: It’s pretty amazing that you wrote the first part of The i Tetralogy over a two-week period.

MF: The very first lines of The Tetralogy were written on the back of a torn envelope retrieved from a glove compartment as I waited for a friend to come home. I began to write and write. When I left him, I wrote for a good part of the night and for most of the week. It was a short novella and really didn’t need much editing. It poured out of me. It was as if I had channeled the contents of my soul in this particular direction. I cannot recall what it felt like, but I can say that I did not have to ponder for a day or week what I was going to say.

I was not concerned with plot or event; I was concerned with saying what I had to say although I did not know what I had to say. I believe it was everything I had experienced as a young boy and man as a Jew; it was as if I had lanced a lifelong abscess.

DA: It’s a remarkable achievement to write the four books of The i Tetralogy without having firsthand experience of the death camps.

MF: Without grandiosity I share what Freud said about his Interpretation of Dreams, to wit, a book like that comes but once in a lifetime. I doubt I will ever again reach such depths as I did with that book –but who knows? One of the gifts of the four volumes was that I took the putty knife and scraped clean the inner windowsills of my self.

The Tetralogy is four books on a related subject. I decided very early on to write volume 2, feeling that I had to strike while the iron was hot, to tell the story now from the point of view of the perpetrator. “i” was told in first person tense from the point of view of the victim. I consciously chose first person for the immediacy of that tense; and that was a killer to do.

It worked! You can taste things in that book, all kinds of sense and feelings. What you are asking is a profound question and I will kick it right back to you, Kafka never was a bug; Melville never was Ahab (or was he?). Acts of imagination can more than compensate for first-hand experience.

Allow me to dig my heels and go deeper. I believe that each of us is capable of being an executioner. I believe man is a damaged creature, he shits and sings from openings. I do not enthrall him. At times I find myself experiencing repugnance as a member of this species. We are invested in our magnitude. I turn rocks over to see the grubs others might choose not to see — that is a writer!

I became a Nazi. I felt what it was to become a Nazi. In the book, I composed Nazi “poetry.” Does this frighten you? Perhaps it should, because I believe there is a Nazi in each of us — loosely tethered at that. The T-Rex in our brain stems, the amygdala in juice. You ask how could people imagine such things? I reply, to wit, because it is in you and it is in me. “On the Holocaust” is a talk I gave on a military base in Arizona in commemoration of the Holocaust. It can be accessed on my website, mathiasfreese.com. I go into it much more deeply. I believe if we take hold of the handrails that line our inner conscious recesses we can walk these cavernous hallways into the darkest recesses of human behavior. Care to join me?

DA: Can you explain why you believe most everything we need to know about nature, and gods, is at the center of the apocalyptic nightmare of the holocaust?

MF: The Holocaust is today; human behavior is today. One of the greatest gifts of Judaism is memory. We don’t put it behind us and get on with it. We process – we metabolize — the past. That is why Jesse Jackson and Mel Gibson so misread Jews.

We remember. I view the Shoah as the quintessential statement of the human race. In it is everything you need to know about the species. “Never Again,” doesn’t even approach the issue. We are dealing with the primal, innate template of each of us — and early reports are that it is metastatic.

In the Raison d’ Etre of the Tetralogy, I write about “the confession” of the Commandant of Auschwitz, Rudolph Hoess, who was required to write it prior to his hanging in 1947. A riveting book, perplexing and reptilian in its fascination, here was a man who had studied to be a seminarian, yet ended his life as a loyal and dedicated Nazi. The book has always stayed in mind, for within its pages is the entire Rosetta stone to the Nazi mind, to humankind gone to seed.

Hoess’s autobiographical tale stayed with me, made a deposit in my unconscious. If I recall correctly, the book is matter-of-fact, which makes it awful. It is descriptive and lacks self-analysis and moral insight. That makes it appalling.

I believe that the Holocaust, if we have centuries to come, will be revisited over and over again for the truths it reveals about human nature — and our species. I believe that the array of human behaviors revealed by the victims, the perpetrators and the bystanders reflects mightily about the inward processes of each one of us. There is no escaping this fact. We flee more from light than darkness. The Holocaust compels us to examine why we behaved and acted in such ways; it goes way beyond the Germans and Nazism. The Holocaust is a Baedecker into the human species. Pause for a second: what about humanity — its gods, its religions, its cultures, arts and so on — is not subsumed under Holocaust?

We are often moral cowards. I choose not to believe that there is a secondary school in this country that has a brave teacher who examines the Holocaust as part and parcel of human nature — oh, no, we escape with political, economic and social causes, all the drivel of intellectually deficient teachers who have to hurry to the next unit plan. I remember teachers spending little time on the Holocaust in social studies classes; I gave it my best effort in English class.

DA: You’ve endured your own tragedies over the years?

MF: What can I say? If you read the autobiographical essay at the end of the Tetralogy I write about the death of my wife and the suicide of my oldest daughter. I have had significant losses in my life, who will not? I go on. Closure is for simpletons. I will go on until it is my turn. What is there to learn from such tragic losses? To move on over the crack in the sidewalk, to take Lipitor, to lose weight and stop smoking. Loss is life’s signal for us to query forever.

DA: Could you elaborate on your notion that language is truly the Internet of the human race?

MF: It’s not called the web for nothing. What I imagine, what I say about what I imagine, is already in you. Human beings are a species that are universally alike; so it is the writer’s task, I feel, to simply have them stand on one strand on the web as I jump up and down on a distant strand, and the ripple effect is sent along and the resonance is felt by all similarly. Language provides that. We are all interlocked in our similar innate traits; the great writer, I imagine, uses that web as a trampoline, the rest of us are happy with a hearty ripple, if that.